Research Projects

We are happy to undertake research projects on behalf of artists’ estates. Two examples of these are Alan Beeton (1880-1942) & Frederick Joss (1908-1967).

Alan Beeton ARA (1880 – 1942)

A brief illustrated biography based on conversations with his late daughter

Alan Beeton was born on 8th February 1880 in Hampstead, London, the son of wealthy parents. His father, dynamic and ebullient, was happy with his situation in life. Forward looking H R Beeton filled his household with interesting people, among them George Bernard Shaw, he had new possessions and new ideas. The family bought an estate, Hammonds in Checkendon near Reading which became the centre of their lives.

Alan was sent to Charterhouse and then to Trinity College, Cambridge. Throughout his school days he drew, sending illustrated letters home from his prep-school and drawing caricatures of the masters at Charterhouse and dons at Trinity. He produced figures with a waspish wit, in a similar style to his contemporary Max Beerbohm, employing humour of observation rather than satire.

He became involved in poster design at which he was extremely competent, with two of his posters being published in The Poster magazine, the first in 1899, a design for the Cambridge Footlights, and then in 1900, a poster from his commissions for Daly’s Theatre in London. This recognition and his desire to become an artist led him to leave Cambridge at the end of his second year, to work as an artist full time.

He left England for Paris and, as was the fashion of the time, studied by taking classes in the studios of working artists.

Alan Beeton in the back seat with his father, his mother and chauffeur in the front c.1902

Gerald Kelly (left) and Alan Beeton (right) in a Paris Studio c.1901

It was during his three years in Paris that he met Gerald Kelly who was to become his closest friend. In the catalogue to his exhibition in 1961 Kelly wrote loyally “In 1900 I went to Paris to learn my job…then one day I got to know an Englishman called Alan Beeton. I was amazed and delighted by what I saw in his studio: here was drawing and painting by a contemporary of mine which delighted me.”

Beeton began to work in colour and with different mediums, his paintings of the time showing the beginning of absorption with technique. They also show a reflection of the life around him – street scenes, peopled interiors; an observant and charming interest in the outside world, unlike his later works. He used a wide range of colours with a strong outline on tinted paper. The pictures are also palpably structured with carefully inter–related blocked shapes; a balance and strength of design we are to see brought forward into the still lives he was to produce in London.

His early still lives were largely in a white, grey and black palette. The design was freer than in his later works, and was essentially about shapes and their inter-connection.

War broke out. Beeton joined first as a private in the infantry then as a captain in the Royal Engineers. He moved across into the Camouflage Unit, part of the Sappers, who were producing camouflage in a small factory just behind the front-line in Aire near Hazebrouck. As well as the artistically technical side of it providing the camouflage was a dangerous job and Beeton was awarded the Military Cross, being mentioned twice in despatches and the Croix de Guerre. He took time out to do his own work alongside.

He was working and living with other artists, among them the woman who was to become his wife, Geneste Penrose, she had studied at the Slade, showing remarkable determination for the daughter of a conventional Cornish family.

Showing further strength of character she joined the Army unlike most contemporary women, who were joining nursing units or the auxiliary corps. Alan and Geneste came back from the war as pacifists, both of them horrified by the whole experience. It bound them together. Beeton proposed and persuaded her parents an artist was a suitable match. He was never in fact a bohemian and had an entirely work-a-day approach to his job. He never attempted to flout convention or do anything other than fit in with his all-absorbing family.

His family was busy and loud and his life was full of people who worked and spent money. He could have made a stand against it and re-invented himself in an artistic style – but he didn’t. Instead he simply continued the family life he had been brought up with. He showed his own nature in his precise style; personally he was neat and particular.

We see from his self-portraits the tidy hair, the suitable clothes – always a tweed suit in the country with a bow tie and a dark suit in Town. He was socially at ease, comfortable in any company. All of which would have helped make him a very successful as a portrait painter – except for the fact he only wanted to paint commissioned portraits if he was interested.

The Beetons set up home in a tall Edwardian house in Hampstead, London. The best room in the house was the studio. Beeton’s father lent them another house, Wheeler’s, on his estate in Berkshire, which they used for summers and holidays and before the children went to school they spent long periods there, decamping completely. Beeton had a second studio set up at the house. In spite of being in the country Beeton never painted outdoors. He never sketched. He never sat outside. His only outside interest was swimming and their annual summer holiday to Cornwall was the only time he went outside, when he swam every day both in the morning and afternoon.

Beeton’s work now had become entirely focused on still lives and portraits. He was a member of the National Portrait Society from 1915. His works show an interest in form and balance and the canvasses frequently employ a triangular composition.

This works through both the still lives and the portraits. He uses a tonal palette, abandoning the range of his Parisian and army work. The tonal range of the colours allows an emphasis on the effects of light. Knowing he had funds behind him, he was able to take time over things and to experiment and work exactly in the way that interested him without the pressure of having to sell.

In this vein Beeton returned to London to work independently as an artist. He painted all day, although the length of the day was dictated by the light – on a dark day he would pack up early. He painted the family servant Pugsley frequently.

The striking profile was executed on brown paper and had been left in the cellar where Beeton’s family found it after his death and had it framed.

He persuaded a tramp to come from the street to sit for him, Lanezzari, was known as Lazarus and became a familiar in the household.

P G Konody writing in The Observer in 1921 proclaimed “In its way this Lazarus is a consummate masterpiece. This low toned painting of an old man, hollow eyed and with sunken cheek, has something of the intense humanity and pathos of a character head by Rembrandt, and shows an understanding of values, of modelling by the relations of tones, that one associates with the art of Whistler, though I should say that Mr Beeton excels Whistler in sureness of craftsmanship.”

He used professional models, such as Rita des Iles, whose portrait he painted in 1923, his first to be shown at the Royal Academy. The Daily Sketch reviewing that year’s exhibition described it as ‘one of the best of the year’. When it was exhibited at the Glasgow Fine Art Society The Scotsman’s critic said ‘the luminously painted face stands out with startling realism from the dark background.’ A different portrait of her was exhibited at the Glasgow Institute, where again it was hung to great critical acclaim.

His fascination with technique and the rigour of his constant search for perfection can be seen in his work in other media: ink, charcoal, crayon and in using different papers as well as canvas. The charcoal figure of a woman manipulates such a dense medium with a wonderful fluidity. A pencil drawing of his father shows the technical diversity he brought even to this minimalistic medium. In his still lives he drew and then produced smaller but precisely finished paintings before setting up a larger canvas to produce a painting on a larger scale. One can see from the painstaking precision of the working painting illustrated that no compromise was allowed at any point in the project.

In his London period Beeton under the aegis of Gerald Kelly had the opportunity to become a society portrait painter, and he started with a few commissioned portraits of society ladies. However he soon eschewed this route in favour his own, chosen subjects. He preferred the challenge of painting local girls or old men to painting society matrons in spite of the commissions offered. Typical is a letter he wrote to Lady Montagu of Beaulieu:

Dear Lady Montagu,

It was very kind of Sir Robert Witt to recommend me and of you to think that you would like me to paint your husband.

I am reluctant to undertake commissions not on grounds of fastidiousness but because I find that conditions of diminished freedom and increased responsibility do not favour the chances of a result satisfactory to me.Considered as a model I am sure Lord Monatagu of Beaulieu would be most interesting; but I am afraid he is a very busy person who would find it inconvenient if not impossible to give me the sittings I might require and although the sort of picture you have in mind is probably a fairly small and simple one, yet I should want a good many (I cannot bind myself to say how many) sittings to carry even a head and shoulders beyond the common place.

…Believe me, Yours very truly,

Alan Beeton

He did bring attention to himself however with his series of lay figure paintings. He painted one initially in 1927 and its success brought him to follow it with more. Amongst these he produced a series of four between 1928 and 1929: Composing, Posing, Reposing, and Decomposing. The idea was novel. It captured attention. P G Konody reviewing them in The Observer asserted:

“It is not so much to the magnificent of array of works by Rembrandt and Hals that the Dutch Exhibition owes its great popularity, but rather to the minute technical perfection and intimate charm of the ‘small masters’. Again and again I have heard the question raised ”Why can’t people paint like that nowadays?”. It was my pleasant experience last week to see in a friend’s studio a series of four little pictures by a living British artist for whom it may be boldly claimed that he has nothing to learn from Vermeer or Terborch or Metsu. The artist’s name is Alan Beeton.”

Posing and Decomposing were exhibited at the Royal Academy in May 1929, The Spectator describing them as “delicate in touch and tone”.

All four were exhibited in the Oldham Gallery in 1930. Decomposing was bought by the Chantrey Bequest in 1931 for the Tate Gallery. Two others went to Gerald Kelly. The series allowed Beeton to execute his skill in reproducing fabric and furniture. The sets for the painting were put together in the London house and Beeton went back to them time and time again, altering tiny details, moving the fold of a piece of fabric, shifting some small object to change emphasis. The minutiae of the interiors were illustrative of his painstaking concentration on detail. The ultimate example of this is his later ‘toy’ canvasses where the heightened detail is truly remarkable. The inanimate of course had the advantage of being both static and endlessly available.

As his parents grew older they were prepared to put in the time to sit for him. There is a striking charcoal of his mother as an old lady. She was deaf, and crippled with arthritis, none of which bodily weakness shows in the face.

As she got older she was happy to be a model, not resenting the being stuck in one place and content to sit still for hours. In general Beeton didn’t paint his family. Nor did he paint children – they were too fidgety and changed within the time it took him to complete a painting.

The reason for the length of time taken on the paintings was the constant re-workings. One of his most impressive portraits was found as a discarded canvas after his death as he had dismissed it as unfinished. It is a portrait of Miss Henderson who he painted frequently. So while to his mind unfinished, which one can see in the arms and the fabric, the whole has a wonderful quality of repose emphasised by the grey blue palette which in its turn also works to highlight the remarkable face. It is interesting to see it in contrast to another portrait Beeton painted of her here we see the emphasis is on the long neck, and the pose is a three quarter face, unusually for Beeton, and the palette is earth coloured. Examining the two together serves to demonstrate how very much the pose, the lighting and the tonality completely alter the portrait proffered perception of the same person. He would break off from a painting to change the colours, sending his wife off to buy new cloth or another piece of clothing in an exact shade to achieve the right colour balance. In one instance whilst doing a painting of Marguerite Kelsey Beeton decided that the velvet of the coat she was wearing was the wrong colour, and work on the painting was halted while Geneste organised with the dressmaker to have another coat in exactly the same shape but a different colour made up. If a cushion in the background didn’t look right to him right even near the end of painting he would Alan_Beetonstop and have it replaced by another which to his eye provided the right emphasis. Some paintings were abandoned altogether after months of work if he felt he couldn’t pull them back into the way he wanted to progress with them. A significant number of his paintings he destroyed. An affable man he never minded being disturbed in his studio, but was distraught if any of the set up for his work was touched. He kept extensive notes on his methodology and it is the relationship between revision and finished effect that was the dialectic of his notebooks. He recorded and reviewed continuously from 1920 till his death in November 1942. His surfaces were constantly stripped down and reworked. Layering was not just adjustment but also experimentation with the effects of literal or perceived depth. For Beeton every day was pursuit of excellence.

After his father’s death in 1934 the family moved to Hammonds full-time. Beeton was not at all interested in the estate. He regarded it as something he had inherited and thus that was to be dealt with conscientiously. The countryside and country occupations had no pull for him. Beeton did see this move as the opportunity to build his dream studio which was built as an extension to the house carefully designed at a particular angle oblique to the house to maximise the north light. Here Beeton worked his daily routine. He never discussed his painting with his family, treating going to the studio in the morning as going to work. He worked with models who he chatted to in the belief their faces were better to paint when animated. One of his favourites, the dancer Marguerite Kelsey recorded later how much she had learnt from Beeton, having spent hours and hours in his company. ’Alan Beeton was my god. I was the only model he ever really used – he painted me for ten years and educated me at Alan_Beetonthe same time. He taught me how to read and write, took me through the classics, showed me how to use a knife and fork in restaurants. I owe him everything.’ (Toby Glanville Last of the Red Hot models in The Artist’s Model p104). He drew first, and then did smaller working paintings before embarking on the final canvas. Although the models were there for a lot of the time, joining the family for lunch as his daughter remembers, he did the bulk of the work with dressed up lay figures, allowing him to work in the detail that so concerned him. Two local favourite models were a gypsy woman and girl who Beeton worked with extensively at Hammonds. The older gypsy, Myrenni, now has her portrait hung in the Master’s Lodge at Trinity, on loan there from the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, to whom it was donated by Lord Rothermere. When the portrait was exhibited at the Royal Academy The Daily Mail critic described it as:

“…approaching perfection as regards subtle modelling, rendering of textures, and true values as far as they can be made compatible with a clearly marked colour pattern.”

The Observer at the time of the gift to the Fitzwilliam wrote:

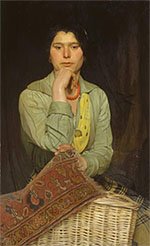

“Even in the work of 17th century Holland it would be difficult to find a passage as perfect as the painting of the little bit of carpet in the girl’s hand. Its appeal to the sense of touch is so strong that in looking at the picture one can absolutely feel the thickness and quality of the pile. The very dust collected in it is unmistakably suggested by the artist’s unrivalled skill in representation. The basket, the material of the blouse, the flesh of face and hands are rendered in the same faultless fashion. With all this Mr. Beeton has not lost his grip on the unity of effect in his attention to minute detail. The picture is painted in a strong direct light which does not allow the introduction of neutral shadows to bind together the contrasts of local colour.The carpet is set against the basket and the blouse, the blouse against the face, the face against the background, in clear silhouette. Yet everything hangs together, thanks to the correct registration of tone values.”

Beeton had noiticed the gypsy girl with her interesting face and approached her about being a model which she then frequently did. The full face portrait shown here again demonstrates his use of a triangular construction. He was perfectly happy to work in isolation from other artists. His measure of success was his own satisfaction with his work. Alan_BeetonFinancially comfortable the urge to find a market never troubled him. His interest was in the process of painting. He didn’t want to take a wider view of his own work, nor did he want to review it in the context of art being produced in a wider world. Any outside judgement of his own work he saw only as of interest in relation to his own view of that work He was utterly not interested in selling. He didn’t see it as an accolade. Occasionally a canvas was sold, the three quarter head of a girl model for instance being bought randomly by the Grafton Gallery. The portrait of Rita des Iles at the Burlington House exhibition had a price of £500 on it. Gerald Kelly included Beeton’s work in exhibitions he put together, such as the Anthology of English Painting, 1900-1931 at the French Gallery, New Bond Street, and the exhibition he put on for Heffers at their new gallery in Cambridge’s Sydney Street. Beeton was a man of simple tastes and simple demands of life. He wasn’t competitive. He was not interested in self-promotion – to the frustration of Gerald Kelly who tried to persuade him otherwise. He had paintings exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1923 through to 1943 and he was pleased when he was appointed an ARA in 1938, but it wasn’t important to him. He never signed his paintings. His daughter says it was to do with modesty – he didn’t see the point of self-advertisement or like the idea of it. One could also argue that he never saw any of his works as finished so never signed them off.

His one politicised work was the major piece he did to vent his private concern for peace in a warmongering world. His biggest hobby was an interest in history. He sat all evening reading. The Beetons were family friends with the Trevelyans with whom Alan would have long discussions. He became involved with the discussion groups pro-peace, for instance lunching with Philip Kerr after his address to the Liberal Summer School in 1933. War Still Life is a precisely worked symbolic illustration of the debates of the day. The centre piece is a significantly round table, with its Arthurian implications as well as the specific contemporary reference to the Round Table movement whose leading members such as Bill Brand, Lionel Curtis and Philip Kerr were fervently anti-war. On it lie the emblems of Alan_Beetonboth peace – Philip Kerr’s tract, The Outlawry of War, Which Way by Bertrand Russell, C E M Joad’s Why War, and of war – the three helmets, the sword and the unopened telegram, with the maps splayed out between them. The table, the library table from the house, was set up in the studio in London over a long period. His daughter remembers the tin hats being around for a long time afterwards and the family still have the sword. In that particularly poignant grouping the symbols would have been recognisable to its contemporary audience, and for posterity Beeton was setting out the anxieties of the time. He offered the canvas as a discussion, and as a warning.

Beeton’s work has been compared, both recently, in the 1920s and in his Times obituary to that of the French neo-classicist Ingres whose precision with texture and light shows similar skills and absorptions as seen in Beeton’s portraits.

It was this absorption that isolated Beeton in his work. It was not that he was shy or anti-social. On the contrary, it was he rather than his wife who invited people for dinner; it was he rather than his wife who spent time with the children. The family as a whole spent time with Beeton’s wider family. It was his work alone that kept him rapt in a constant quest. The marriage was such that he and his wife were happy together in a quiet way. No-one ever raised a voice and nothing difficult wrinkled the fabric of their easy life. The house was lovely. It was Alan and Geneste’s first opportunity to spend money for themselves and they enjoyed it. Beeton chose to hang some of his pictures in the house when he was pleased with them. Occasionally one was sold to a friend. Beeton went up to London frequently to see people but mainly to get materials that he wanted to choose himself. The other materials were ordered by his wife or bought by her locally. Beeton always visited the framers himself.

Early in his career, as we have seen with the Footlights posters and the Parisian works Beeton was in tune with the times. Take, for example, the portrait painted in 1923.

Here the model holds a copy of Vogue and by the style of the clothes and the stance of the body one can date the portrait instinctively. The lettering on the pencil, ink & crayon portrait of his father again shows his ability to link into the stylistic nuance of that year. His charcoal picture of the lone woman has empathy with the contemporary work of Wyndham Lewis and Augustus John. However by the second half of mid 1920s Beeton’s solitary occupation whilst having no effect on his affable nature, affected his work by allowing the slowness of his method to produce works in an uninterrupted series in terms of style and technique. He worked tirelessly on what was effectively one long project entirely unique to him in both its execution and conception. His lack of contact with other artists quite possibly added to his dedication to one goal and thus his reluctance to explore other areas and develop his work in other ways.

In his last years he suffered a debilitation which he met by painting less in a day rather than stopping, or taking breaks. His quest was undiminished. He kept on painting until he died. After he died his family emptied out the canvas store. There was a mound of paintings stuffed together randomly. They discovered a treasure of canvasses his perfectionism hadn’t thought fit to see the light of day.

Several works by Beeton were exhibited in the very successful exhibition Silent Partners: Artist and Mannequin from Function to Fetish at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (14 October 2014 – 25 January 2015), which won the Apollo Award for exhibition of the year. The exhibition then moved to the Musee Bourdelle, Paris (1 April – 12 July 2015).